Peter Joseph Crombet-Beolens (1918-2000)

| Parents | ‘Pete‘ | Win | |

| Siblings | Eric | Rita | |

| Partners | Rosemary | ||

| Children | Rhiannon |

Peter (foreground) with Rita, Eric & Pets

In his own words

MEMORIES AND IMPRESSIONS by Peter Crombet-Beolens

As I have just finished writing a few pages recording my mother’s recollections of her early life, I have been persuaded to write down some account of my own memories. The family interest in its antecedents has led some of my cousins to research our genealogy quite seriously, and this has sparked my interest, especially since Mum’s 100th birthday, which was attended by over a hundred New Zealand relatives, so I feel compelled to start by giving some background before coming to my own existence.

I was surprised to find that the old family names of Rawlins and Gambling are of Norman origin, but I like to think that my mother’s family blood comes mainly from ancient indigenous stock that were farming the south-west of Britain long before the Normans arrived. In any case, patronymics clearly tell less than half the story. Although my mother was born in Hutton, near Weston super Mare in Somerset, her grandparents were both born in Wiltshire, her mother in Salisbury and her father elsewhere in the same county. Her brothers and sisters all appear to have been born in the same general area, and many of their descendants still live there, though many others have emigrated to various parts of Canada, the USA, Australia and New Zealand.

My father was born in Willesden, London, of Dutch parents from the Hague and Groningen, so I can claim to be half Dutch by blood. Since my parents moved to Hove, in Sussex, shortly before I was born, then moved when I was only three years old to the country between Lewes and Uckfield in the same county, I have always felt to some extent separated from my roots, but even more alienated from the surroundings in which I found myself. This feeling was no doubt accentuated by the fact that in those days people moved about much less than they do nowadays, and ‘off- comers’ were not always made to feel at home or welcomed by small country communities.

I was born on 14 January 1918 in a small flat in Leighton Road, Hove, but have no recollection at all of that place. My first memory is of getting up into the cab of a removal van that took us to our new home in March 1921. This must have been a great occasion with a feeling of adventure for me, for a fleeting impression of its novelty still remains. The new sights and sounds of the journey are a blur, but I must have enjoyed the experience because travel has been a joy to me ever since, regardless of discomfort. Nothing else of that day can be recalled, but my mother still remembers that on arrival I could not believe that I was encouraged to go outside to play. The change of environment from a cramped apartment in town to a house on an acre or so of land in open country must have been amazing.

Our council house was number 7b of a small group of eight or so semi-detached dwellings, each with its ‘old-fashioned’ acre, on the Uckfield Road, about two and a half miles from Lewes. These ‘Holdings’ were provided for ex-service men and their families in the attempt to get them rehabilitated after the First World War. My father had been badly wounded in 1917, having lost an eye and suffered serious skull fractures as well as injuries to his left arm when run over by a gun-carriage drawn by frightened mules, but he had recovered sufficiently to attempt to run the smallholding by raising chicken and growing crops.

MY PARENTS

My father was born on the first day of August 1890, and may have been of the type described nowadays as ‘hyperactive’. Certainly, he was said to have sworn like a seasoned trooper at the age of four, later injured a schoolmate on the jaw with the edge of a slate, took up smoking as a child and evidently became something of a trial to his parents. His father seems to have taken an early opportunity to apprentice him to a racing stable as a stable lad, and he became a jockey. I believe he was based at Maison Lafitte, Longchamps, where he learned to speak French fluently. He evidently travelled about Europe to race meetings, and we still have a photo of him that was used as a postcard postmarked ‘Hoppegarten b. Berlin 18.3.13’. His service papers later show him as speaking ‘German, Dutch, Flemish and French’, though Dutch was the first language of his parents and Flemish is essentially the same language.

He was very small in build, being only 4 ft 11 ins in height and slight in proportion. Like many small people, he had a ‘large’ outgoing personality and tended to be somewhat aggressive, mercurial and excitable. He could dress well if occasion required it, but was conmonly very untidy when at home. I remember when I was trying to help him plant out some vegetable seedlings and he swore at me as useless. He was often short-tempered and foul-mouthed, and at times, as a sensitive lad, I loathed him intensely, but he had his good points.

In spite of being quite poor, he was generous to a fault and was keen to encourage me to learn. This showed itself when I was about seven or eight, I think. I had learned to read well early on, and by then read anything I could get hold of, even trying to read some old Dutch books he still had, one of which was ‘Tooneelspielers’, apparently a book of one-act plays or about repertory players as far as I can remember. He then gave me a set of Arthur Mee’s ‘Children’s Encyclopaedia’, which I proceeded to read voraciously from the beginning of the first heavy volume to the index that took up half the tenth. Each chapter was about a specific subject, starting with first principles in the first volume, and working up to a more advanced level in the last, so that each volume contained a whole range of subjects from Archaeology to Zoology. This was truly a revelation that opened up the world to me, and I shall always be grateful for this.

My mother evidently started life as a quiet country girl who ‘wouldn’t say boo to a goose’, to use her own words. Life with my father, however, must have been a hard school, and she soon learned to stand up for herself. Always a hard worker, she had to do more than her share with a disabled husband, and became the mainstay of our home. Not only did she eventually raise three of us children, cook, wash and care for all of us, but did a good deal of the work on the smallholding as well. Fortunately, she always loved gardening and caring for chicken, ducks or geese.

EARLY DAYS

Memories of my childhood are fragmentary and composed of only a few impressions. My brother Eric was not born until I was seven and a half, and there were few children among the neighbours, who kept to themselves anyway, so I grew up as a quiet and self- contained child and something of a loner. One of our more distant neighbours was a Scot who lived about a mile away. Mr Macdougal played the bagpipes occasionally, and I remember when I first heard the distant sound of pipes with a strange thrill. I have always loved the sound, but I showed off and said something like, “What’s that bloody awful noise?” I believe it was a lament.

My first experience of Ringmer School at the age of five was evidently a shock to my system, as I distinguished myself by being disastrously incontinent. I still remember coming back from the lavatory and being shown a trail of little ash-covered piles across the schoolroom floor. Fortunately, I must have got over the shock fairly quickly, for most other memories of school are comparatively pleasant. These are mostly vivid sense impressions of colour and smell, like the exciting colours of crayons and the earthy smell of natural local Weald Clay that we used for modelling. It was kept damp in a large tub with sacking over it.

My early reading had already given me a fairly sophisticated vocabulary for a country child, though I still mispronounced a number of words. I remember answering some question or other by saying, ‘Not partic’larly’, and this seemed to amuse the group of teachers who got me to repeat it. I must have learned fairly quickly and easily, and got on well with most of them. Before I left, however, I ran across a bad-tempered one by the name of Mr Blundell, who on one occasion seized my right ear and led me out to the front of the class. I believe I may have been a bit smart, but I hadn’t gone out of my way to annoy him.

I remember walking along the mile and a half of country lanes to and from, school, often accompanied by other children who lived in the same direction. One of the Robbins girls took a fancy to me, but it was far too early for me to take any interest, and I repelled her advances. I was very shy and unused to girls. We used to eat hips and haws from the hedgerows, being careful to split open the rosehips and extract the hairy seeds. We called the leaves and fruit of the hawthorn ’bread and cheese’ and ate them together after taking out the seed, but it was unexciting fare. Other things in the hedges like Jack-in-the-pulpit (Arum) we left severely alone, as we knew them to be poisonous, but we loved to find newts, frogspawn and tadpoles in the ditches, and. took them home in jam jars.

The headmaster was a Mr Gurr, who was keen to perpetuate or revive old country customs like Maypole dancing on the village green, and I remember taking part, weaving in and out among the other dancers, each holding a coloured ribbon attached to the top of the pole to produce a plaited pattern. I believe Mr Gurr was an ‘offcomer’ like myself, but he took an interest in the Sussex countryside and its ancient history.

These interested me too, and the village forge opposite the school, with its smell of singed hoof when the hot shoe was applied, the ringing anvil and the piles of differently sized horseshoes and cartwheel rims, was a magnet to a young child like myself. About a quarter of a mile east of the school was a pub called ‘The Green Man’, with an inn sign showing a jolly looking man astride a barrel, dressed entirely in green leaves. This fascinated me, though I did not then suspect that there were many other pubs with the same name scattered all over Britain, or that they were connected with ancient pagan fertility belief. In recent years, I have made the Green Man the subject of some research.

Just beyond the inn was a road junction where the straight two miles of road to the northeast called the Broyle met another road to the east. At the junction was Ringmer Kennels where the foxhounds were kept. We often heard these baying and belling at feeding time. Less pleasant was the squealing of pigs being slaughtered at the slaughterhouse by the lane on the way home. There was evidently no idea of humane methods being used then. Other sounds that come to mind were the skylarks that rose from the meadows until they were lost to sight but still clearly heard. At home, nightingales sang in the dusk in water meadows at the bottom of our narrow strip of land and thrushes and blackbirds rivaled them during the daytime. Not far away was another stretch of marshy land where peewits gathered.

The Holdings were on the Lower Greensand of the Weald, and the soil was therefore light and well-drained but ‘hungry’, needing plenty of feeding all the time and sometimes watering in dry weather. I remember one occasion when we sank a pit about five feet deep to tap the underground water. We normally relied on a communal well and a pump that sometimes ran dry, and in hard winters we had to raise the manhole and break the ice several feet below ground level before we could raise the water in buckets. This was our only source of drinking water, as we had no running water in the houses. The lavatories were part of the houses, but had a separate door so that we had to go outside, and were equipped with large buckets that had to be emptied and the contents buried.

Occasionally, we came across ‘shepherds’ crowns‘ or fossil flint sea-urchins, and I eagerly collected these, as well as others from uncles’ land in the West Country. From my reading, I knew them to be Cretaceous fossils and therefore over 60 million years old, and they formed the nucleus of a collection of fossils and minerals that was eventually the focus of my geological studies, Our southern and western horizons were bounded by the chalk hills of the South Downs, their scarp slopes pocked here and there by chalk pits, and leading up to gentler slopes crowned by ancient mounds called barrows. Climbing up to them, the backward view was of the gently undulating Gault and Greensand country leading to the distant woodlands of the Weald and the sandstone hills around Crowborough.

Rudyard Kipling lived only a few miles away at Burwash (which we called ‘Burrash’), and he described this Wealden country well in poems and short stories, though as a member of the Ringmer Wolfcub Pack I first got to know his Jungle Book stories about Mowgli. I went to two camps in the holidays, one at Midhurst in West Sussex, about seven miles from the Hampshire border, the other at Instow, near Bideford in North Devon, which was the furthest I had been from home. The only thing I can remember now is the size of the cobbles on the beach we visited. I was used to the Brighton pebbles, but these stones were up to six inches (15 cm.) across. The cubs taught me a number of useful things, though I never achieved any badges as far as I can remember.

I remember he was very strict about cleanliness, and particularly about washing hands after going to the latrine. The cubs taught me a number of useful things, though I never achieved any badges as far as I can remember.

A troop of scouts from Brighton or Hove used to camp on the Humphreys’ land not far away during the holidays, and my parents used to help out by providing vegetables and so on. The scout-master was a kindly man named Morgan Smyth, and I often visited the camp, especially with my half-cousins Harry and Len Upton when they stayed with us for a week or so, their mother Ella was the daughter of Dad’s mother after she married a man named Whitlock, and they came down from London occasionally, just as we sometimes stayed with them during the holidays. Paddington was another new experience for me, though probably not unlike the part of Hove where I was born, but could not remember.

An attractive part of the upper River Ouse was only about half a mile away across the fields, and I first learned to swim in its somewhat muddy water, often ‘skinny dipping’. This slow meandering stream was quite safe, though it had some holes that were suitable for diving practice, and it was only some 49 to 59 Feet across at this point. We occasionally tried fishing there, but the only thing I ever caught there was an eel about three feet long. About a mile upstream was the pretty settlement of Barcombe Mills, where we could take out flat-bottomed boats for a small charge and paddle them up and down the branching waterways.

During the depression of the mid-twenties, attempts were made to rehabilitate many miners from South Wales by relocating them in areas where there was more chance of employment, and in particular using their labour for maintaining and improving roads in Southeast England. My parents were asked if they could accommodate some of these men, and four were billeted on us. I found their strange accents fascinating, and took to them immediately. Eric was born about this time, and my mother must have found catering for four hungry men as well as my father and two children a considerable strain, although the extra money coming in must have helped matters a bit.

I remember David Hughes in particular, a fairly tall, thin man with black, curly hair who was known as ‘Dai’ (short for David). He claimed to be something of a medium, and we had several table-rapping sessions in the evenings which I felt a bit spooky. Bill Edwards was more thickset and less charismatic, but very friendly and pleasant. Wyndham Rickson was short and lightly built and seemed somewhat better educated than the others. He had worked in a tinplate factory or foundry. I can’t remember much about the other man. They all left us eventually for one reason or another, and Dai started working in the Lewes Cement Works at Southerham, where he eventually had a fatal accident.

CHARACTERS

At one stage before he left us, Dai fell in with a strange crowd who turned up at Wellingham House in the lane beyond the stream, about half a mile from where we lived. These were bohemian types who included a minor poet by the name of Hedgell and Betty May, a model who achieved some small fame in the early twenties, when she was involved with the infamous Aleister Crowley, her husband [missing text?]

‘Thelena” on Sicily in February 1923 in somewhat suspicious circumstances, Betty May wrote about all this in her autobiography ‘Tiger Wonan’,

They turned up sometimes at our local pub called the ‘Cock Inn’ and they visited us on one occasion. I believe they were into drugs, and certainly drank a lot. Anyway, they got poor Dai paralytically drunk, apparently on methylated spirits according to one account, but he recovered well enough. I think one of them may well have laced his drink with some drug.

It seems to me now that over the years a number of strange people impinged on our lives in one way or another. Some were lodgers or guests, some were distant relatives and some were old acquaintances of my father. He had the faculty of attracting to himself odd or colourful personalities, some of whom I never met, but who remain in my memory as faded photos or mpressions gained from Dad’s stories. Some of these were unlikely, as I never knew whether he was relating something that actually happened or was merely a figment of a creative imagination. Some were only too likely. One of his old cronies was a Dicky Dunn (or Donne?) now commemorated in a couple of photographs, one of which was a comic set-up showing him and Dad as emerging from the broken halves of a giant papier maché eggshell.

‘Doss’ Chirgwin was an old school friend of my father who was the widow of the music hall artist well-known at the turn of the century as ‘the White-eyed Kaffir’. She occasionally visited us at 7b with her two children. Auntie Bella was Dad’s half-sister, who had married Harry Upton, the illegitimate son of a Jewish nurse. He brought into our lives a few of his friends and relatives, one of whom we got to know as ‘Auntie Shonky’. Her husband was a somewhat vague individual who was said to ‘talk in riddles’, whether he was some kind of mystic or seer, or merely lived in a world of his own,

Ted Normington was another ex-serviceman who had lost an arm just below the elbow and had developed an amazing knack of doing things with his one good arm and hand like knotting a tie loosely over his stump, throwing it over his head and tightening it round his neck. I also remember him as expert at shuffling and dealing cards with one hand. He was also a bit of a ‘fly boy’ who was not above doing a few things on or over the edge of the law. On one occasion, a headlight bulb blew on our car, and he replaced it by taking one from a nearby unattended car while he got me to keep a lookout for him. If he got in a scrap, he took the hand off his artificial arm and used the aluminium end of it as a weapon. I must say, though, that he was a pleasant fellow in my experience, and good company apart from his tendency to involve people in his shadier activities.

An even more dubious character who turned up later as an indigent seeker for work and shelter was George Guthrie, though I’m not sure this was his real name. At one time he used the name of Boulton. He was an Australian, and I sometimes wondered whether he might have had to get out of his home country in a hurry. George was a tall, lanky man with a long jaw and usually wore a sardonic grin. He had a hole near the spine at the small of his back that one could put a thumb into. This apparently resulted from treatment for meningitis when spinal fluid had to be drawn.

He had evidently spent much of his early life on the edge of poverty (and probably the law) and spoke of having lived on rotten bananas and got what he called ‘banana ferment’. His stories also included accounts of hunting ‘Abos’, whom he clearly regarded as less than human. He took a job as a milker on a nearby farm, and was somewhat better off by the time he left us. The last I heard of him, he was a used car salesman in Bristol.

LEWES

Lewes is an ancient town, with a ruined castle keep that dominates it when seen from a distance, and many old houses that in some cases date back to the fourteenth century. They are of varied construction, some half timbered, some faced with hung tiles, some of knapped flint. Near the station are the ruined priory that dates back to 1077 and Anne of Cleves’ house that is now a museum. The grammar school was founded in the 16th century.

The great traditional event of the year in Lewes is Bonfire Night. Although this has many features that recall the pagan Festival of Samhain, it is nowadays overwhelmingly anti-Papist and ostensibly commemorates the Gunpowder Plot. There is an obelisk on the slope of the hill called Cuilfail, overlooking the Cliffe, that commemorates a number of Protestant martyrs that were burnt at the stake in Lewes, and this may explain the feeling against Catholicisn that still pervades the celebrations.

Mock trials are held, and effigies of both Guy Fawkes and the Pope are regularly burnt at the fires of about half a dozen Bonfire Societies. The members of these work throughout the year to raise money, create costumes and tableaux for the torchlight processions that parade through the streets, meeting at the war memorial at the top of School Hill where a communal ceremony is held, then taking separate ways to their traditional sites where each Society holds another rite and lights its fire and tableau or effigy. Some sites are high on the Downs, near the Lewes Racecourse for example. This is above Offham Hill and near the site of the 1264 Battle of Lewes. Each Society also has its own tradition of costumes that are often elaborate and handed down from one generation to the next. I think it is the Borough Bonfire Society that specialises in Red Indian costumes, while others dress up as cowboys, pirates, smugglers, Vikings and so on,

One old tradition that may indicate a pagan origin was the rolling of a lighted tar-barrel down the steep School Hill and dowsing it in the River Ouse at Cliffe Bridge, but this was finally banned as an unjustifiable hazard. It was similar to other traditional ‘fire and water’ customs involving blazing wheels held elsewhere in Britain and Europe. The festivities are not usually rowdy, but some casualties have resulted from throwing lighted fireworks about, and this is also banned. Shopkeepers wisely put up their shutters anyway.

WIDER HORIZONS

When I was about eleven years old, I took an examination for a scholarship that would entitle me to further education, as most people then left school at the age of fourteen. As far as I can remember, it was a simple intelligence test with multichoice questions, but it turned out that I was the first child at Ringmer School to be successful. My parents were overjoyed though it meant an increased commitment and expense for them.

I first went to Brighton, Hove and Sussex Grammar School, a large five- or six-storey building with a clock tower in Dyke Road, Brighton. After cycling the two and a half miles to Lewes station, I took the train for 15 or 20 minutes to Brighton, then either walked or took a bus to Dyke Road. I was put into Form 2R (Remove), where I first started to learn new subjects like French, algebra, geometry, science and ancient history. I remember that the French master was from southern France, that we did not learn Latin as that was-taught only in the upper school, that some pupils were boarders who looked down on day boys like myself and that there was organised bullying in the playground, but little else remains in my memory of experiences there. This is because I was there for only one year, as boys who lived nearer Lewes were given the opportunity of transferring to the Lewes Secondary School for Boys that had just been completed. From then on, I had only to cycle from home to Lewes, avoiding the expense of train fares. However, by the time I was thirteen, Eric started going to school, and for some time I gave him a a lift on the carrier of my bike, making a detour via Ringmer and adding a couple of miles to my journey. Eventually, he got used to the idea of attending school and managed to make his own way there.

My new school was a one-storey brick building near Lewes railway station that looked out over The Brooks, an expanse of water-meadows bordering the tidal Ouse south of the town. The classrooms, offices and laboratories were arranged in two squares separated by the gymnasium, all joined by covered walkways like cloisters round the two lawns. The first intake of pupils came from various schools round about or from entirely new entrants. We were divided into about five ‘houses’ according to the areas we came from. Thus, pupils from Uckfield were assigned to Uckfield House, but those who, like myself, came from various country districts were called ‘Martlets’, after the landless Saxon knights who took the heraldic symbol of birds without feet. The school badge represented the castle keep with six martlets at the foot.

As at the Brighton Grammar School, the masters all taught in gowns, assuming their hoods and mortar-boards for special occasions. They stayed in the rooms assigned to them, and bells rang at the end of each period as the signal for the pupils to rush from one room or laboratory to another.

I missed out on Latin, as it was at first taught only in the first forms to avoid the confusion of different pronunciations and teaching methods used by previous schools, then continuing in the higher forms in successive years. If I had stayed at Brighton, I would have started learning it the following year, but at Lewes it was always taught in the form lower than the one I was in. I went on learning French, however, and later had a year of German, but dropped out of that as I did not get on with it so well. I took it up later after leaving school. My bugbear was history. We had been taught ancient history at Brighton, and I had enjoyed it, but I found British and European history dull. I eventually managed to get a pass in School Certificate history, but credits in all my other subjects. I still have the Oxford University matriculation certificate, which looks quite imposing compared with its modern equivalents.

Apart from German and history, I got on well, especially enjoying chemistry and laboratory work in general. The only time I distinguished myself in the lab was when I was assisting the chemistry master with some complicated tall apparatus he had spent some time making. Of course, I managed to break it, and it took me some time to live down my public display of clumsiness.

I continued my experimenting at home as soon as I could scrape together enough money to buy some simple apparatus and chemicals. It was easy enough in those days to buy quite dangerous substances like corrosive acids, poisons and caustic alkalis, and I shudder to think now how I endangered my health by making fumes and gases without the benefit of a fume cupboard. I later heated lead and mercury for example, heedless of the danger of poisoning myself, and graduated to making my own fireworks. This was quite successful until the day I used a short fuse that at first refused to light and then the firework suddenly blew up in my face. I was fortunately wearing glasses, or I would almost certainly have been blinded, as the lenses were completely coated with fused saltpetre. As it was, I temporarily lost my eyebrows and had a painful face for several days. I wisely gave up making fireworks then.

My folks’ resources were already severely stretched, so I took no part in the holiday trips arranged by the school, which were usually abroad. For the same reason, I did not go to the opera at the Glyndebourne Festival when John Christie first founded it in 1934, though we were given the opportunity to do so. This was just as well, as it was then a very ‘stuffed shirt’ affair, and I would have been totally out of my depth.

I was sixteen then, and had taken the School Certificate exam, gaining credits in English, mathematics, science, geography, French and art, and a pass in history. This gave me Matriculation with Honours, which could have entitled me to go to Oxford University except that I had no Latin, which was then regarded as necessary for a tertiary education. I stayed at school for almost another year to study higher math and science, but also took a Civil Service examination that I just scraped through. I knew I had not done as well as I should otherwise have done as I was quite ill that year, though I never discovered exactly what was wrong with me.

While waiting for the results of the exam, I took a job in the East Sussex County Library as an assistant librarian. This was poorly paid and involved a good deal of quite menial work heaving heavy cases of books that had been circulated round the county to small village libraries, checking them in and replacing them on the shelves. Partly because I was below par, but perhaps also because I found the work uninspiring, I did not do at all well there. I did enjoy the access to as many books as I could take home, though. There was an extremely good selection of a wide variety of books, and it was common for several copies of a book likely to be at all popular to be bought, in order to cater for all the local libraries that we supplied. My tastes ran to less popular non-fiction, however, and it was there that I developed a particular fascination for so-called ‘occult’ books. Many of those on the shelves were on theosophy and I became well versed. As well as less well-known authors on similar subjects.

TELEPHONES

Eventually, I was accepted as a Clerical Officer in the Brighton Telephone Manager’s Office, and once again found myself cycling to Lewes station to catch the train to Brighton and walk or bus to Dyke Road. The Traffic Office was housed in Totteridge, an old-fashioned house with a square tower little more than a hundred yards from the Grammar School I had attended some five years or so previously.

The telephone system in Britain was at that time run by the Post Office and was therefore part of the Civil Service. The Traffic Office was responsible for measuring and estimating the telephone ‘traffic’ passing along the lines and through the exchanges in the Brighton District, which covered Sussex and parts of Surrey and Kent, and forecasting the current and future requirements of exchange buildings and equipment, lines, cables and duct. This was a quite crucial function in those days, as routing was rigid and both equipment and connections were dedicated to carrying specific traffic. Any alteration had to be carried out physically by engineers and was expensive. Each part of the system had to be tailored as exactly as possible to the traffic it was expected to carry to avoid both wastage of unnecessary plant and overloading due to insufficient provision. At the same time, provision had to be made for expansion, and growth foreseen, so that extension of equipment and provision of extra circuits could be carried out efficiently.

This work required close cooperation with both engineers and exchange operating staff and involved careful measuring and calculation. I had found myself unsuited to any ordinary clerical job, and enjoyed the semi-technical nature of the work. I also found the people I worked with to be congenial for the most part, We had little in the way of office machinery in those days, and had to rely on simple ‘plus-adders’ and the occasional mechanical calculator, but our constant companions were slide rules, capacity tables and math tables.

The basic unit we constantly had to deal with was the ”erlang’, which is theoretically the traffic that fully occupies one circuit. This sounds simple enough, but in practice involves taking into account the random nature of calls being made at any moment and lasting for any length of time. Capacity tables therefore have to be based on probability. Provision of circuits is based on the ‘busy hour’ because of the importance of ensuring that delay is kept to a minimum. when most calls are being made, usually between about 9 am and 10.30 am. During the remaining 24 hours, especially at night, the system is used much less, and lower charges are imposed to encourage people to make calls then, so that the traffic is evened out to some extent.

So much for a greatly simplified overview of telephone traffic! Practical application depended on considerable knowledge of the way exchanges work, and I started to study operational telecommunications in my spare time. The new job’s major impact on my life, however, was the important matter of pay, and this was much more than the pittance I had been getting in the library at Lewes. I remember looking at my first Brighton pay packet and wondering how I was going to spend it all! This euphoria did not last long, however, for of course I had to pay my parents for my keep while I was at home.

SPARE TIME ACTIVITIES

Nevertheless, I soon started buying a two-seater folding canoe on hire purchase. This was of rubberised canvas over a flexible wooden frame, and proved to be less portable than I had hoped. I could manage to lug it to the river with some difficulty, and I had a lot of fun with it on various stretches of the Ouse, but I found it easier to carry to the coast in my parents’ car. We occasionally went down to Seaford, Newhaven or Bishopstone on weekends, and I found it quite exciting when the Channel steamers came in and created fairly high waves. I had to be careful not to get swamped, as the rubberised hull was quite heavy and would have sunk like a stone.

By this time, Eric was about nine or ten and Margaret was about five years old, and they enjoyed being given a ride in the boat. I sometimes took Eric down to the Ouse with me and showed him how to use the double-bladed paddles, so that we eventually made much better time up and down the river. We had one accident when we went over a small weir near Hansey island where the river had cut off one of its meanders by a straight section. I had gone over this before by way of ‘shooting the rapids’, but on this occasion went over the wrong side and hit a snag that ripped the bottom of the boat, making a tear about a foot long. The canoe filled rapidly, and I just managed to get out, seize both Eric and thecanoe and kick out desperately for the bank.

Fortunately, it wasn’t far, and the water quickly became more shallow and I was able to wade. It was easy enough to get Eric on the bank that was low at this point, but the waterlogged canoe was a dead weight. However, I managed to drag it out and empty it, then found a piece of flat board that I was able to jam under the framework against the tear. This enabled us to paddle upstrean. for the mile or so to our landing place near home, with only a slow leak that made us bail occasionally. I eventually made a good repair with a heavy-duty canvas and rubber patch.

About this time, Eric also acquired a bike and I taught him to ride so that we were able to cycle further afield. We soon visited places like the Long Man of Wilmington, the ancient figure carved in the turf of the Downs about fourteen miles away. Nearer at hand were the chalk pits below Malling Hill, where we chiselled fossils out of the chalk boulders and flint nodules. I also practised using a small box camera, getting my innocent brother to stand in exciting looking places on the edges of crumbling cliffs. I’m afraid I was a dangerous companion, as I also showed him some of any chemistry experiments, like making chlorine gas. On one occasion I held my thumb on top of a test tube a bit too long when I invited him to smell it, and he took some time to recover from coughing. I was only able to offer him a drink of water, but that helped him get over it. He must have had a charmed life.

During school holidays, we sometimes accompanied Mum and Dad on journeys to Hampshire to visit Mum’s brothers and sisters and their families, particularly Uncle George and Uncle Sid as I remember. We had a Citroen at that time, that was a bit troublesome at the start, but went much better after it had been running for some time as the compression improved. We only ever had one serious breakdown when we had to stay overnight at a little place called Botley near Southanpton.

AWAY ALONE

It was not until 1938 that I first went off on holiday alone, taking a cycling trip down to Cornwall and back, using Youth Hostels for my overnight stays. The rest of the family went off the same day to Hampshire, so I was able to strap my bike to the roof rack of their car and get a lift for the first hundred miles to a little beyond Lyndhurst in the New Forest. This was a great help, as it enabled me to cover more new ground that I had never seen before. I went right down to Lands End and visited several places I had read about and wanted to see for myself, such as Stonehenge, Tintagel and Glastonbury, covering about 700 miles. I have described this holiday more fully in ‘Southwest England’, which I wrote to accompany the set of black and white photos I took on the journey. These were not very good, but I valued them as a record of my first holiday alone.

The following year, I cycled north to the English Lake District, once more using Youth Hostels for overnight accommodation. My main purpose was to explore that particular area, so I lost as little time as possible getting there and back. I have very little record of that holiday as I took no photos, relying on picture postcards only. I found Cumbria, as it is called now, more challenging than Cornwall because it is much more rugged. I often found myself walking more than riding because of the steepness and roughness of the roads. These have no doubt been improved out of recognition by now, but then Hardknott Pass, for example, was often crossed by gullies and strewn with stones and even boulders.

I soon realised I was in wonderful walking country, and people I met in the more rugged places persuaded me that next time I went there I should leave my bike at home, travel up by train and walk the mountains that were inaccessible to a cyclist. This is what I did, but it was not to be for several years, for the Second World War intervened.

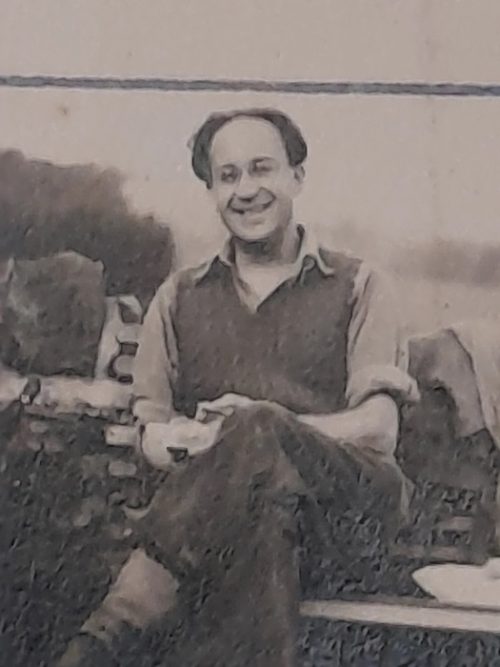

Sometime in the 1940s

IN DIGS AND THEN AT WAR

In 1938, the Brighton Telephone District had been split into two, and I was transferred to the new Tunbridge Wells Area. This was when I had to leave home and start living in lodgings. The first place I stayed was in Lime Hill Road with a widow and her daughter. There were two other lodgers there, one of them a policeman who got engaged to the daughter, and the other a tailor whose fiancée called now and then. I found this an uninspiring place for some reason, and soon moved to stay with Mr and Mrs Mann, who were a really lovely couple. Mr Mann was a retired plumber who had apparently contracted lead poisoning because of his work.

One advantage I found was that I now had only a short distance to go to work, I still used my bike, but sometimes walked to the top of the town, where the Traffic Office was in another old building called Northbrook House, rather similar to Totteridge. My work was still very much the same as it had been at Brighton, and some of the staff were the same, so I had no difficulty settling in. I found living in a town an improvement from the point of view of amenities, though Tunbridge Wells was at that time very restrictive at weekends. There was absolutely nothing open on a Sunday except the pubs and churches, and even their ‘opening times’ were restricted. I had no taste for either, so I was often at a loss unless I took the bus home to visit the folks.

This situation soon came to an end, however, though the change was not a welcome one. The war started in September 1939, and I was called up in January 1940. Because of poor eyesight, I was put into the Royal Army Pay Corps, a non-combatant unit, and sent to Hastings. I had asked to go into the Royal Corps of Signals, but was not considered fit enough at that time. The authorities became much less fussy about eyesight or anything else as time went on, but I was stuck in the 33rd Battalion of the RAPC for my whole service as it turned out.

My new companions were a scruffy and nondescript bunch, especially as we had no uniforms for a long time, and arms drill was sometimes with broom handles. There were no barracks for us, and we were ‘billeted out’ in digs. The first place we were allocated was with a cadaverous man with sunken cheeks and a pale complexion. His wife was slightly more healthy looking, but they provided us with really terrible food. The meat was all gristle and the vegetables were literally rotten. We were there only about a week before we rebelled and found a new place where for the same money we were well fed and housed. The women there were really nice to us and looked after us well.

This idyllic state of affairs lasted only until May, when our forces were driven back to the Dunkirk beachhead and we could hear the guns on the other side of the Channel. There were no air raids as yet, and the war had been a phoney one as far as we were concerned. The only signs of defences were a few pillboxes and some barbed wire apart from the strange tall ‘radio’ masts or towers on a hill to the west of us. We learned later that these were the prototype of radar that was to play a major role in the Battle of Britain that still lay in the future.

The authorities lost no time in transferring our unit to London, and we arrived there to the cold comfort of an empty barracks with about a quarter inch of dust on the floor. This provided extra insulation from the concrete as we laid our blankets on top of it. Fortunately, the weather was not cold and we had only one night there. We were quickly allocated new digs that proved satisfactory and once more settled into a routine. It was then that I met Ivor Thomas from Hirwaen near Aberdare, South Wales.

Like Dai, he had black curly hair, but was about my own height and sturdily built, though his disability consisted of a bad shoulder joint that had been damaged by heavy work making bricks. His shoulder made a clearly audible grinding noise that put my teeth on edge when he moved his arm. He was cheerful and friendly and I took to him at once. As soon as he was able, he brought his wife up to London, installing her in a fourth floor flat in Islington, and invited me to stay with them.

Phyl was a very pleasant dark woman who spoke fluent Welsh and immediately started teaching me a little of the language. I got on well with both of them, and we had a good time exploring London. Phyl found a job in a factory in North London that made wire and rubberised canvas items like heavy duty watting for tanks and other vehicles. I helped occasionally with a few chores but found that my flatmates were happy with the extra bit of money I contributed to running expenses. I got used to climbing up the four flights of concrete stairs with sacks of coal for the fire, just as I became accustomed to the stoking and coke-heaving fatigues in the boiler-room at work.

I had gravitated to doing construction and repair work in the pioneer workshop in the basement as being more congenial than the dull writing duties of the clerks upstairs, eternally entering innumerable pay and allowance slips in the heavy ledgers. We were housed in a nine-floor building in Finsbury Circus that had belonged to the Bank of England, two of the floors being below ground and housing vaults that we used as armouries for rifles, handguns and ammunition. A big building like this took a good deal of maintenance, though I’m afraid some of our work was more destructive than constructive. Signs and noticeboards were made of teak and mahogany, and those that were of no use to the army were commandeered and sawn up for new purposes.

In spite of rationing, our existence was not too austere, though it was a job to make the minute allocations of foodstuffs go around when at home, it was still possible to go out to restaurants and get a reasonable meal, and occasionally we visited service canteens of one sort or another, apart from our own at Finsbury Circus. There were occasional concerts and shows, and plenty of cinemas for entertainment. Ivor was fonder of pubs than I was, but I accompanied him. on a number of pub-crawls. Highgate Hill was not far away, and this seemed to have a pub every few yards all the way up.

We also visited Camden Town, the Irish part of London, and kept quiet when the locals fulminated about the ‘bloody Black-and-Tans’, staring challengingly round the bar and itching for a barney. Paddington is known as the Welsh quarter, but Highgate has its own Welsh community too, and we occasionally went to meetings of Welsh clubs as well as Methodist services, though Ivor was a Baptist. London seemed to be the world in miniature, especially as many Polish servicemen, Austrian refugees and other foreign nationals gravitated to various parts of the capital.

As the war progressed, our training became more warlike, and marching and drill became exercises in unarmed warfare, street fighting and target practice. We were also subjected occasionally to simulated gas attacks, though the tear gas was real enough, and we had lectures on landmines and other anti-personnel devices. We found that things were getting worse and we were expected to be ready for invasion, and the threat was in everybody’s mind. We also became aware that there was a very real fifth column in our midst. Not only were many of the London Irish disaffected, but one civilian who at one time shared our accommodation was openly pro-German.

THE ‘BLITZ’

This was really a misnomer. Even the term ‘Battle of Britain’ is a bit misleading, as a ‘battle’ is normally a comparatively short engagement. A Blitzkrieg is a ‘lightning war’, the idea being to take an overwhelming attack and gain immediate victory. The London ‘Blitz’ lasted for months and months on end; in fact, it went on intermittently in one form or another from September 1940 to mid 1944, It was in September 1940 that the massive daylight air raid took place, apparently with the German intention of frightening the living daylights out of the civilian population. When the sirens went off, nothing prepared us for the sight of wave after wave of enemy aircraft that filled the sky. Compared with the night raids that came shortly after, it did little real damage, even to civilian morale. The few British fighters did far more damage to the Germans, I believe.

However, the night raid on the City a little later did enormous damage. Incendiaries and high explosives rained down on the city until whole streets were wiped out. From our roof in north London, our southern horizon was one blaze from end to end, and when we went in in the morning we had to negotiate a maze of rubble, fire hoses and ladders, with still soaking ruins all round us. We eventually became used to seeing bizarre sights like buildings that seemed to have been sliced vertically in half to reveal pictures hanging on wallpapered interior walls on second or third floors with clocks still on the mantelpiece, or baths hanging by their plumbing out of bathrooms revealed to the public gaze.

There were times when the bombing went on night after night without ceasing, and enemy planes no longer concentrated on the City, but bombed the rest of Greater London indiscriminately, so that nobody was safe anywhere in the capital. We often saw the whole show from the grandstand of our office roof, seven storeys up, when we were on firewatch with a ridiculous stirrup pump and bucket, as if we would have been able to extinguish an incendiary bomb by spitting on it. Sometimes the firework display was incredible. While the sky was split by searchlights, the bombers rained down their bombs, apparently oblivious of the barrage of anti-aircraft fire. Occasional flares lit up the scene, and chains of glowing beads that we called ‘flaming onions’ shot upward. I still do not know what they were, perhaps something experimental. Meanwhile, most of the ‘shrapnel’ that fell around us seemed to be jagged shell splinters from our own anti-aircraft fire, still almost red hot. It would have been ironic to get hit by ‘friendly’ fire.

I often found myself going home during an air raid, reciting the 23rd Psalm. like a mantra: “Yea, though I walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death, I shall fear no evil…’. I was rarely in a shelter for one reason or another, perhaps because I felt they were often too flimsy a protection. There was the hit on the Bank Tube Station to demonstrate this, when a large number of people were killed because the shelter was only just below ground level.

In the midst of all this, life went on. I started going out with a girl of my own age who worked at the same factory as Phyll. She was almost too slim and had fair hair and fancied herself as a singer. She too came from South Wales and spoke Welsh fluently, as did the rest of her family. There was the old father, a stolid elder brother, an unattractive elder sister and a very attractive younger sister of about 17 years of age. I fell secretly in love with the latter, but Kay was altogether too fiercely possessive, and threatened early on to throw herself off a bridge if I did not continue going out with her, though I had not given her any reason to take such an extreme step. I should have taken no notice of this, but gave in to the moral blackmail. I’m afraid it was a story with a sad ending, because after continuing the affair for some time, I could stand it no longer, and ended it. I should have had the courage to make some kind of pass at the younger sister, because I think she rather fancied me for some inscrutable reason. I heard later that she had run off with a Polish serviceman.

Sometime later, I fell in with a buxom English girl called Doris and for some time went to concerts with her as we were both fond of classical music. Her mother made me most welcome at her home, and treated me to some great home cooking. I was very keen on Doris and wanted to marry her, but her brother came home on leave and for some reason or other evidently warned her off me. I was quite cut up when she said she liked going out with me, but didn’t want to marry me, Mistake number two. I should have gone along with this, and tried to bring her round eventually, for I think we could have got on well together.

After a lull in the conventional air raids, Germany started launching the V1 flying bombs in mid 1944. These could sometimes be more than a little scary. Normally, they would fly a straight course, the motor would cut out and they would dive and explode, but sometimes they would come overhead and start to pass on, then turn and come back, the motor would cut out and they would dive. They were not designed to do this, but had been upset by our fighters attempting to put them off course.

Far less alarming were the V2 rockets; these were much larger and carried more explosive, but they came so fast that they outstripped their own sound, and the first thing you knew, they had exploded. It only remained to breathe a sigh of relief and thank heavens it wasn’t you. One phenomenon I noticed has not been mentioned by anyone else: the explosion was followed by the diminishing sound of the thing going back up into the sky. There would be the sound of a rushing express train gradually receding into a distant whisper. I noticed this before I knew what the things were and before I heard anything about their speed, but evidently the sound lagged behind the weapon, remaining audible afterwards,

By the end of the war, a great deal of demolition had been carried out, so that in place of the ruined buildings lay cleared sites with the deep basements left as great square pits in the ground. Some areas, notably around St Pauls, which miraculously escaped any major damage, were now great open spaces in place of crowded buildings, so that Wren’s cathedral was open to view for the first time in many decades,

Very gradually, life started to return to normal, but it was a very long time before rationing eased and servicemen were able to return to civilian life. As I was one of the earlier men to be called up, I was de-mobbed in June 1946, and left London to go back home on extended leave before returning to Tunbridge Wells.

On a walking holiday

1954 7B ‘Front room’

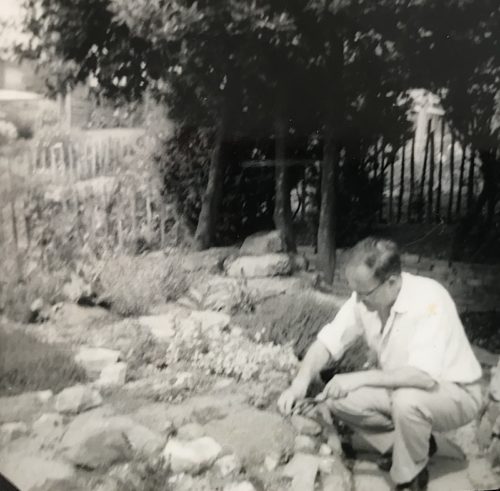

Peter planting his rock garden in Tunbridge Wells c. 1963 – Each plant was labelled and some were collected in the field

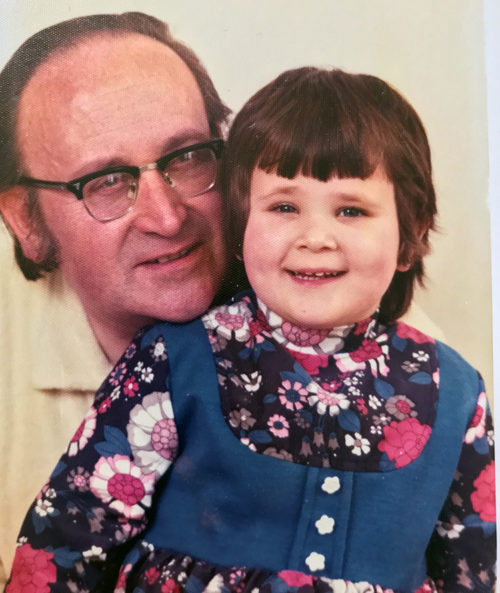

Peter with Rhiannon

Rhiannon’s University Graduation 1991

At his mum’s 100th Birthday Party