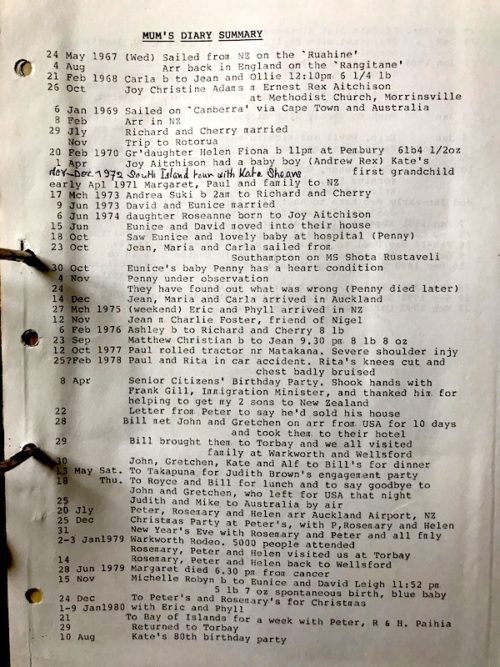

Ethel Winifred ‘Win’ Crombet-Beolens née Rawlins (1897-2001)

Win Rawlins

|

Parents |

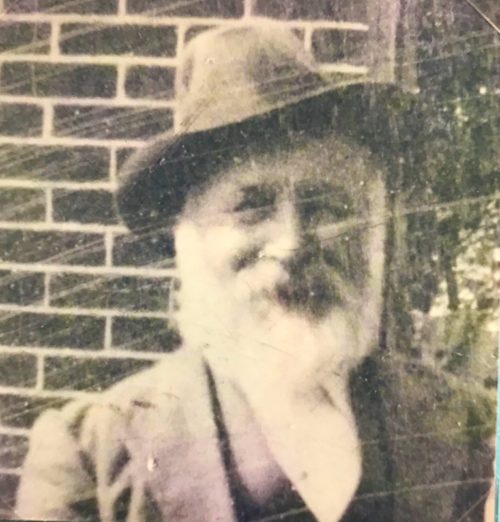

Arthur William Rawlins (1858-1940) |

Rose Hellen Gambling (1858-1915) |

Married 1881 |

|

Siblings |

James Artur Nutley Gambling (1879-1963) (m.Catherine), Harriett Mary (1881-1882), George Edward (1883-1965) (m.Lena Drew), Edith Lydia Ellen (1884-1958) (m.Rivers Francis) |

Alice Annie (1885-1888), Albert Victor Gordon ‘Bert‘ (1887-1942), Alvah Dan Eustace DCM (1889-1915), Nellie Evelyn (1891-1989) (m.John Edward Cochie or Cockie) |

Silas Sydney Mark (1893-1938), Rosa Ella ‘Rosie‘ (1895-1966), Still born twins (1898), Kate Hilda Caroline (1900-1991)(m.Alfred Shears) |

|

Partners |

Peter Joseph Crombet ‘Pete‘ Boelens |

|

|

|

Children |

Father – Arthur William Rawlins (1858-1940)

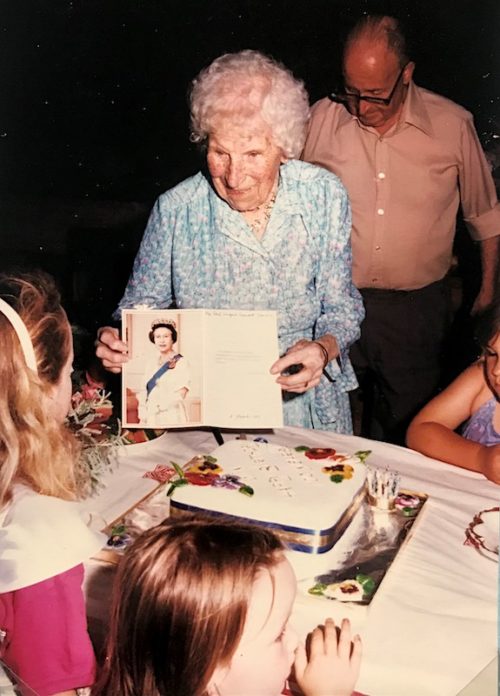

Win at 100 years old

Showing the letter from the Queen

Read down the page to learn about gran’s life in her own words, also see what she wrote about her wartime occupation by clicking the link below:

The Wartime Flax Factory Near Uckfield, Sussex

In her own words…

It was 1901 when Queen Victoria died, so I was four years old then. I can’t be sure, but I think at that time we were living at Urket (spelt Uquhart?) Lodge. It had the tall fancy gates that were used then at the beginning of the drive up to the Big House. Then we lived in a cottage further up in the woods where we had a big Labrador dog. The keeper had words with Mum, as he said the dog ran about in the woods and caught or frightened the pheasants. Anyway, Mum had three or four hives of bees at the top of the garden by the beginning of the woods, and someone had put some poisoned stuff on their food and killed the lot. Of course, Mum blamed the keeper.

I was born at Hutton, a small place near Weston-Super-Mare in Somerset, on 2 March 1897, when Queen Victoria was on the throne. When I was two years old, I’m told, Mum made me some ‘pap’ (bread broken up, covered with milk and some sugar and beaten up in a cup). I went outdoors with the cup in my hand and a spoon to eat the pap with. I fell, broke the cup and cut the side of my nose. I had it stitched, and the scar did not entirely disappear until about a couple of years ago. My first clear recollection was when I was just over four years old, as my late sister Rosie, who was two years older than me, was pushing my baby sister, who was three years younger than me, in a pram. I was walking beside it along a road, when I heard some small animal squeal in the hedge and I was scared.

I don’t seem to remember the next place we went to, but it may have been Broad Chalke or Bowerchalke [7 to 9 miles WSW of Salisbury, Wilts]. They were not far apart (2 miles). I remember one day I was told the ‘faggots’ were coming, so always being a good eater, I went out with a fairly big plate, and one of the others said “What have you got the plate for?” I said, “For the faggots”, and they said, “It’s the firewood faggots, not the meat ones!” You can guess I was disappointed.

The farm was not far from us, so we used to go down and play in the cart shed, which was built with one side open so that carts, wagons and elevators etc. could be pushed in and out of the snow and rain. Rosie and I were playing, digging in the dust holes, trying to build ‘sand castles’. I was scraping out a dust hole and found a sixpence, so you can guess at that age I was rich. We often used to ride the horses around to keep the sheaves going up on the elevator to the ricks (stacks). I remember I was sitting behind Rosie, hanging on to her waist, and when we got back to the farm she loosened the reins by the pond for the horse to have a drink. I was afraid I would slip off and fall into the pond myself.

I also remember when my eldest sister was away working. For Christmas she sent us a cardboard box of lovely decorated pink and white sugar animals tied up with coloured ribbons for the Tree, and some jelly animals. I particularly liked the jelly crocodile. We pulled the tail up to its nose and watched it as it slowly straightened itself. I seem to remember some icing sugar ornaments with coloured pictures in the centre too. As well as little coloureds candles, we also had small oblong chocolates covered with coloured foil and tied up with coloured ribbons to hang on the Christmas Tree. My, we were excited. I have never forgotten the white sugar mice. When we hung up our stockings by our beds, they were filled up with some nuts in the toe, some sweets, an apple and an orange and just one small gift. We didn’t get a lot, and didn’t expect it, but were quite happy and had fun and games. For our Christmas dinner, we had a joint of beef, pork or ham, Christmas pudding, mince pies, etc.

Much later, my daughter Margaret used to fill up her boys’ stockings with toys for a dollar. She was shocked when she first arrived in New Zealand to find what it cost to fill a child’s Christmas stocking. She had been used to filling one up with sixpenny toys of every description. When I got out here, children had started hanging up pillowcases. I was disgusted, and thought how greedy they were.

How different prices are now! It’s the same all the world over; prices have gone mad. I don’t see the reason or sense of it. We are living beyond our means and aiming too high for things we could do without. The mighty dollar is ruling the world and we are no happier.

At Bowerchalke, we lived in a cottage by a beautiful clear stream that had big clean stones on the bottom. We kids went in with bare feet and helped to hold the stones up for our older brother. There were fresh eels under the big stones, and Sid was able to dig down and catch the eels with a carving fork. Then he cut the skin round the neck and slid the skin inside out. Then they were cut up in thick rounds and either fried or made into a stew with milk thickened with flour. Lower down the stream, the owner had watercress beds and planks across the stream to walk on to gather the cress. Our garden was across the road, and it had two or three fruit trees there. Our town was Salisbury, a cathedral town, where we went in by ‘carrier’ for shopping and so on.

I remember we wore black sashes over our white starched broderie l’anglaise pinafores to school. We used to wear black stockings buttoned up to a liberty bodice. Our knickers were buttoned up to them, gathered up on bands, two button holes in front and three at the back to fasten on to the buttons. We used to exercise in the playground using broom handles. For games, we used to tear up our old exercise writing books and play Hare and Hounds in the woods nearby, scattering the paper as we ran and leaving a trail to be followed.

One place we lived, we had to walk three and a half miles to school. I think it was at Nutbourne near Clanville, Hants. [This was near the Wiltshire border about three miles NW of Andover.] Just down the road from us was a crossroads where one road led to Clanville, another to Andover and a smaller road led to our school. A big cluster of beautifully scented white violets grew on the corner, and we used to pick them for Bert. Further along was the Big House with large iron gates where notices were put up each day when the King or Queen was ill. They also provided a large soup kitchen. The soup was lovely with plenty of dumplings. Once a week we used to take down our milk cans to be filled up, and we carried them home.

George was a gamekeeper at Wilbury Lodge, Newton Toney, Wiltshire. As gamekeeper, he bred and took care of game (pheasants etc.) and prevented poaching. We had a pheasant breeding run guarded on each of four sides by a dog leashed to a running wire that did not allow them to get close enough to each other to fight. The pheasants’ nesting boxes were padlocked and the earth round the run was pummelled hard to discourage rats from digging under the wire. Bert worked for a time as under keeper. After one shoot, he held out a couple of pheasants to some girls who were passing and said jokingly, “How would you like a couple of these my dear?” Another worker nearby said to him, “Shut up , you fool, that’s Princess Alice …” I can’t remember who Bert worked for, but he joined a Scottish regiment. George and Lena invited me to stay with them on holidays, and it was there that I learned to ride a bike. My sister Rosie taught me on the long drive from Wilbury Lodge to the village. Later, when George bought his farm, I remember that Lena made lovely butter.

I saw John Cockie only once at Wilbury Lodge, but remember that Nellie used to look after kiddies at Bulford Camp, where she became a Christadelphian (she had been “chapel” like the rest of the family). Bulford is very close to Stonehenge, and Newton Toney is about 3 miles further east and about 9 miles north east of Salisbury. It is still a very small place, I believe.

We also lived for a time at Timsbury [two or three miles NW of Romsey]. The school was not far from the railway, and the head teacher’s name was something like Mrs Kitcat. She was a very small woman with long hair she could sit on and used to get very bad headaches. Her son’s name was Horace and she was very strict with him, punishing him more than the rest of us. We used to be sorry for him if he didn’t get his lessons right. Perhaps she was training him to be a headmaster some day.

There were all boys in Dad’s family, his three brothers being Dan, Eustace and Mark. Dan worked for years in Salisbury Cathedral; he had no children. All the family were musical, and Dad played the melodeon and accordion by ear. He used to get drunk on Saturday nights, which eventually led to his downfall. This was why we had to move so often. He was not a heavy drinker, but could not take much. His brother Caleb was quite well off and was at first generous to him, but he kept losing jobs because of drunkenness. Otherwise he was a good worker, and was still a skilled hedger, thatcher and ditcher in his seventies when he fell of a haystack and broke his collarbone.

There were 5 brothers and 5 girls altogether in Mum’s family. Mum had a hernia, dropsy, asthma and heart trouble and she died at 57 years of age. George’s wife Lena had a sister

Polly who didn’t marry, and two brothers, all chapel people. Their family name was Drew. We still have a faded old photograph of George and Lena outside their bungalow sitting at a table in the garden with Polly, my mother (Helen Rawlins), Lena’s brother David, who was a chapel preacher, and niece Gladys Drew. Lena became ill with Parkinson’s disease (called palsy in those days) and was bedridden for years. George had to employ a housekeeper called Alice, whom he married after Lena died.

I can’t remember when Nellie emigrated, but it was after Edie had gone to Canada with Rivers, who was a cabinet maker. In those days, such craftsmen often picked their own timber in the rough before it was sawn, and he was manhandling logs when he damaged his heart. Edie (prior to this) was pregnant with her first child and asked Nellie to come from England and stay in Canada a while, so this must have been in 1908 or early 1909. It was in Canada that Nellie met John Cockie, and when Edie returned to England with Rivers when he had damaged his heart, Nellie stayed in Canada, of course. Edie took up laundry work. I remember Edie ironing and goffering with the sweat streaming down her face. It was pretty hard work in those days, with no ‘mod cons’, just fetching water in buckets for the copper in which the water was heated, hand washing, mangling and ironing. The irons were heated on a small chunky stove about 18 inches square. Rivers collected and delivered the laundry in a handcart. He later kept chickens.

Of course, most of you don’t go back as far as I do; your lives are in another climate and the seasons are different. I came out here by ship when I was 70 years old. I do miss the old-fashioned coal or log fires and going out to get the Christmas Tree, holly, ivy and mistletoe.

In those days, all our travelling was by bicycles, horse and trap or shays, or horse-drawn ‘carrier’ to town once a week for shopping. Otherwise, we went to nearer shops with a child’s pram. When we were near Hursley, northeast of Romsey, we had to go four and a half miles each way. The first motor vehicle I saw was one of my older brother’s motor bike and sidecar, but I was in my teens then. This was about the time I remember seeing the bulletins about the illness of King Edward VII posted up on the lodge gates. He died in 1910, and I was thirteen or fourteen when I saw my first aeroplane. I think it may have been when King George V was crowned in 1911. We all went to the coronation celebrations in Christchurch, where there was an aeroplane display, and the memory is linked with the fact that I didn’t get a coronation mug that was given to children still at school.

I was 14 years old by then and was working at my first job, looking after two little girls for the Randalls, who had a shop near Christchurch, so I could not have the nerve to ask for a Coronation mug. A few mugs I did have I gave to Eric.

We were living at East Parley then, and I remember my Uncle Caleb Gambling was on a visit from Thornley, near Sydney, Australia. I only saw him one day that I had off from work. Uncle Caleb had no children, and I used to write to him. He had lovely handwriting. He had a brother Ted in Queensland who had several children including one girl. Later, Mum’s legs became bad, and to help her I had to leave my job and stay at home for a while.

Then I got another job helping a housekeeper whose boss was a widower with two sons running a big fruit shop. I had such a bad back working so hard Mum took me away from there. Then I worked in Edie’s laundry and lived in with her. My health was not too good. I got a nasty big boil on the base of my thumb. The doctor came in, took my arm under his so I couldn’t see what he was doing and lanced it without anaesthetic, so I had to work with one hand. Later, I had another ulcer come up on my knee and I had difficulty walking, so they sent me home. They thought I would have to go into hospital, but Mum looked after me well and made me lie down on the sofa.

One day the vicar called. He said they wanted another maid, and would Mum let me go there when I was fit. I worked at the vicarage at West Parley for 3 years when I was 14 to 16 years old. The church was only across a stream. I used to go over the stream there, through Moordown and on to Bournemouth shopping. I lived with the vicar’s family and used to walk home by the river when I could to see my mother, as it wasn’t far. When the vicar’s 19-year-old sister got married, I was given a brooch decorated with a thistle all in silver, the two flower heads being of amethyst and citrine, and the surrounding oval was set with flat, narrow oblong stones. (The amethyst and citrine eventually got lost over the years.) The other maid was given one just like it. The man the sister married had a stipend for a church in the Bahamas, where they emigrated. I later went back to help Edie at her laundry, as it was getting a bit too much for her.

Bert and Alf both came over to see me at the vicarage when they were on leave from Egypt and India (1912). They both looked very smart. Two years later, they were among the first to be called up and sent overseas. What they did in between I don’t know. I do not know much about them, though I do remember them being home for a while. Sid also went into the army later, and I still have a photo of him in tropical kit with a pith helmet, so he must have been abroad too at some time. As for Jim, I could have passed him in the street and not recognised him, though I think he was tall and thin. He was very close to his brother George, who was thickset. Jim used to stay with George a day or so, but as you know, travelling was not easy in those days and they lived near Bath. I never saw his family, but I used to write to his daughter Cathleen.

When the First World War started, we women all wore long dresses. Then food was rationed: two ounces of cheese, butter, tea etc., and queue for extra margarine, golden syrup, sugar, and particularly for meat etc. Coupons for clothing, and later on bread for fourpence a loaf, streaky bacon fourpence a pound, eggs twopence each, milk twopence a pint. We lived in the country and always had a good garden so that was a great help.

Alf died in France in 1915. He had won the D.C.M. and been made a sergeant on the field, but he was supposed to be coming home on furlough, and when my mother received a telegram she thought it was to say when he would arrive, but it was to say he had been “killed in action”. My mother had brought up a family of five sons and five girls, and at 57 had several serious medical problems. She could not get over the shock, and died three months later.

Alf used to go out looking for snipers, and on this occasion one of his pals said he shouldn’t go but let someone else go instead. Alf said, “No, I’ll go. It might as well be me”. So out he went and got a bullet in his arm. The wound was poisoned or infected and they had to amputate, but the poisoning spread. He had written to Mum saying “I am in hospital and can see the sea from here. Luckier than Bert who had bad flesh wounds. Get a bottle of pickled onions ready for me. I won’t be long.”

It was while at the vicarage that I met Pete who was in the army at a camp near Romsey. He was a roughrider in the RASC, breaking in horses and mules. I used to see him once a month, when I went to Romsey every other month, cycling 7 miles through the forest to Brockenhurst, where I went on by train. Pete used to come to meet me at Brockenhurst on the other months. I went to live at Romsey and think I was there for about two years. We got married in February 1917.

Soon after we were married, Pete was handling mules when they were spooked and bolted. One man was killed and Pete was run over by the gun carriage they were drawing. He had serious skull fractures and lost an eye, as well as injuries to his left arm that were expected to leave him permanently disabled. I had already lost my mother and my brother Alf in 1915, and now this.

About a month after he came off the danger list, he was sent to a ‘convalescent hospital’ on Sir George Cooper’s estate where he could be with other men and where they could stay until they were fit to go home. I think there were about 20 men there. I went to stay with my sister Rosie at Hursley as it was closer, and she went to see him first as she did not want me to be given a shock. When she came back, she told me I would be able to see only his lips, as he had lost one eye, and a wound that crossed his nose to a hole on the other side had to be dressed every day and covered up with an irrigation tube leading into it from a bottle at the top of his bed. He was lying on a pile of moss pillows to soak up the fluid.

Then I started to cycle down there on Rosie’s bicycle and sat by his side. After several days, he looked up to the ceiling and said “What’s that up there Win?” I said, “That’s a cloth hung over the lampshade to save your eye from the glare.” So, he gradually got better, and when he was able to see and chat with the other fellows and didn’t really need me there, he suggested that I should stop cycling over to the hospital as it was no longer safe in my condition. Also, Rosie had a house full of people, so I could not go on staying there. He told me I should go to Hove in Sussex and stay with his mother. I did so when I was about four months pregnant, so that was how Peter was born in Hove.

I remember that two weeks before Peter was born, I stood in line for two hours for a minute piece of butter, and was almost dropping when I got it. Pete’s mother lived in a flat in Leighton Road, but eventually moved to London, and I took over the flat. I had been paying 5 shillings for two rooms, but had to pay 10 shillings a week for the flat. Pete was discharged from hospital in October and from the army as ‘unfit for service’ on 19 December 1917.

Peter was born at 3 Leighton Road, Hove, in January 1918. He was only about three years and two months old when we moved to 7b Holdings, near Lewes, so it was a new world for him after living in a town flat. At first he asked if he could go outside to play, but soon got used to the wider surroundings. We lived there from March 1921 till 1962, keeping chickens and growing vegetables on about an acre of land. During the Depression, we lodged four miners from South Wales for a time: David Hughes (Dai), Wyndham Rickson, Bill Edwards and another man whose name I can’t remember. Later, Dai was killed in an accident at the Cement works.

It was shortly after the war ended that Nellie and John Cockie went to England (on holiday?). I thought there might be a photo somewhere of John Cockie or one of my brothers with George, holding a brace of dead pheasants, but it turned out to be Bert (in uniform) with George, and they were holding rabbits!

John Cockie went to work in the USA while still in Canada, but had to wait 2 years for a permit to live in the USA. (1927-9?) Of my brothers, Bert had 2 years’ service in Egypt, Alf had 2 years in India, and I remember when they were both home on leave at the same time. Alf (Alva) was the one who died of wounds in 1915, and I think he was buried at Wimereux. I remember he was only 26 when he died, unmarried. Sid’s eldest daughter was named Rosie and then he had a son John. Maisie was a younger daughter and then there was Joyce. I have a photo that I think is of Sid with three of his children, a boy, maybe John, (about 11 or 12?) and a girl of about 3 or 4 years (Maisie?) and a child in arms (Joyce?).

Eric was born at 7b Holdings in 1925 and Margaret in 1930. They were both baptised in Ringmer Church and went to school at Ringmer, and Margaret was married in Ringmer Church. Jean, the only daughter of Eric and Phyll, was also born at 7b Holdings as Eric was overseas in WWII, and so did not set up home at that time. He got a job at Wiston near Steyning, and Richard was born there. After his discharge, Eric passed an exam for the Police Force and lived around Faversham for a short while, then went to West Malling near Maidstone, and afterwards to Snodland until his retirement, when he emigrated to New Zealand. Pete died in 1962 at the age of 72. I left 7b a year after Pete died. They would not allow widows to take over the Holdings.

Gran’s Diary when she emigrated at the age of 72